Rosenbach (2002) gives a clear introduction to the historical development of the genitive variation. Rosenbach (2002: 177-178) summarizes that in Old English the of-genitive was mainly used to indicate source or partitive relations, and only constituted 1% of all adnominal genitive constructions. In Old English there is a word order option of placing possessor prenominally or postnominally, yet the of-genitive has not yet become a viable grammatical variant. Rosenbach (2002: 178) states that in Old English the postnominal genitive was rapidly replaced by the prenominal genitive, and animacy was a decisive factor. Thomas (1931: 105-106) concludes that the loss of article/determiner, strong adjective inflection and the shift towards fixed word order to indicate grammatical relations might have led to the restriction to prenominal genitives.

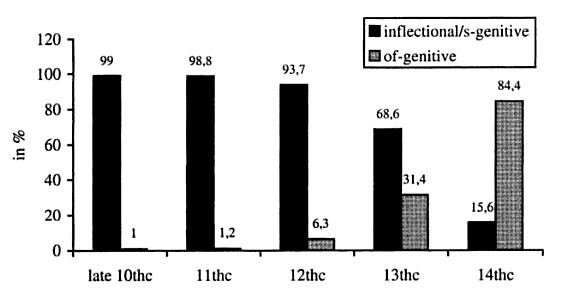

During the Middle English period the s-genitive gradually declined. The distribution of the s-genitive and the of-genitive from the late 10th to the 14th century has been presented in a figure by Thomas (1931) through corpus analysis. The distribution of the two genitives is shown below in figure 1.

Figure 1. Distribution of the s-genitive and the of-genitive from the late 10th to the 14th century (Thomas 1931; taken from Rosenbach 2002: 179)

As shown in figure 1, the s-genitive dominated in the period of the late 10th to 12th centuries. From the 12th to 13th centuries, the proportion of s-genitives declined from 93.7% to 68.6%. Later, during the 14th century, the s-genitive (the proportion of which was only 15.6%) was largely substituted by the of-genitive. Mustanoja (1960: 74) assumes that the spread of the of-genitive might be due to the similarity to French de, yet Thomas (1931: 120) suggests that it was structural reasons that caused the increased usage of the of-genitive. Thomas explains that the reasons could be the loss of inflection in definite articles and strong adjectives, and the increased use of the periphrastic genitive. In the period of Middle English, the s-genitive became restricted to proper names and personal-noun possessors. In addition, it also became restricted to certain genitive functions, i.e. the possessive and the subjective function (cf. Fischer 1992: 226-227).

In early Modern English, there was a revival of the s-genitive. Rosenbach and Vezzosi (2000) present the evidence for the revival of the s-genitive through analyzing a corpus of prose texts from the period 1400 to 1630. Rosenbach and Vezzosi (2000) divide this period into 4 synchronic stages: 1400 – 1449, 1450 – 1499, 1500 – 1559 and 1560 – 1630. They found out that the proportion of s-genitive usage increased from 8% in the first interval (1400 - 1449) to 19.1% in the last interval (1560 - 1630). Rosenbach (2002) considers that the revival of the s-genitive is “surprising” (Rosenbach 2002: 187). Rosenbach (2002: 187-188) argues a more rigid word order developed (Subject-Verb-Object) from Old English to Middle English, hence the s-genitive, as a synthetic device, should have further decreased. Also, VO-languages like English are typically head-first, hence “head - modifier” is the common order for possessum and possessor (of-genitive: head - modifier [possessum - possessor]). Above all, Rosenbach (2002: 188) concludes that the revival of the s-genitive is an unexpected development.

In Present-Day English, the s-genitive is increasingly popular, especially in American English (Rosenbach 2002). Leech and Smith (2006) think that the rise of the s-genitive could be due to colloquialization and Americanization. Hinrichs and Szmrecsanyi (2007: 442) give a definition of the term Americanization: “’Americanization’ refers to a frequently corresponding phenomenon that has been found to be at work for many of these features: alternatively called the ‘follow-my-leader’ pattern of British English, it typically describes processes of colloquialization which are led by American English (…)” Yet Hinrichs and Szmrecsanyi (2007) argue that the wide spread of the s-genitive in Present-Day English might be due to a process of economization rather than colloquialization and Americanization. Hinrichs and Szmrecsanyi (2007: 467-469) offer two reasons to support their argument: one reason is that NPs which have a high text frequency in a given corpus text favor the s-genitive in the 1990s data (Frown and F-LOB) more often than in the 1960s data (Brown and LOB). Hinrichs and Szmrecsanyi (2007: 467) suggest that “when writing about a noun or NP repeatedly, why not just as well use the economical s-genitive with that noun or NP?” Another reason is the type-token ratio, i.e. Hinrichs and Szmrecsanyi (2007: 457) suggest that the s-genitive would be preferred in the contexts which have high lexical density. Hinrichs and Szmrecsanyi (2007: 457) also mention that, “the more different word types we find in a given passage, the higher the lexical density and the more pressing the need to code economically.” And “writers prefer the more compact coding option in lexically more dense environments” (467).

Hinrichs and Szmrecsanyi (2007: 469) conclude that there are 4 reasons which explain the more frequent use of the s-genitive in American English press texts than in British English press texts. First, the s-genitive is less constrained by the factor animacy in American English press texts. Second, American writers tend to code highly thematic possessors with the s-genitive. Thirdly, American writers pay more attention to the factor weight: when there is a long possessum, they more frequently use the s-genitive. Lastly, American English press texts have a higher type-token ratio, which favors the s-genitive.

Created with the Personal Edition of HelpNDoc: Full featured multi-format Help generator