The problem of defining an adequate number of informants poses many difficulties similar to the ones presented by the issue of defining an ideal interview length. Obviously, a large number of informants makes for a highly representative sample (see sampling here). But having large amounts of data also requires much dedication on the fieldworker's part as transcribing and analysing said data may turn out to be a painstaking affair. Therefore, Tagliamonte (cf. 2006: 32-33) agrees with Feagin's (cf. 2002: 21) statement that, in terms of transcription and analysis, having a smaller, better circumscribed amount of data is to be preferred over having too much data due to time and funding constraints. However, one must be sure not to have too small of a sample as this will invite (justified) criticism. Famous examples of successful research are provided by Labov (1966) and Trudgill (1974). Labov interviewed 88 informants from New York City and Trudgill observed 60 people from Norwich (cf. Milroy and Gordon 2001: 29).

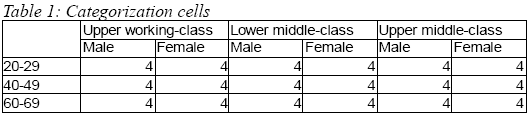

Tagliamonte (cf. 2001: 31) as well as Milroy and Gordon (cf. 2001: 29) point out that categorizing the informants into groups consisting of cells and then filling these cells with three to five people is the best way of collecting data. For example, if someone were to interview people (male and female) from three different social backgrounds and consisting of three different age-groups, he/she would wind up with a total of 18 cells. Assuming that each cell were to contain four people, this would result in a required number of 72 participants as depicted in Table 1.

If a researcher were to add another category, for example ethnicity, with three further subclasses, he/she would either have to interview three times as many informants or reduce the number of informants per cell.

Created with the Personal Edition of HelpNDoc: Easy CHM and documentation editor